Conclusion

The rise of political extremism in the United States cannot be understood in isolation from the structural features of its electoral system. Over the past decades, factors such as gerrymandering, closed primaries, the influence of dark money, and the decline of moderates have fundamentally distorted representation in Congress. These mechanisms reward ideological rigidity and punish compromise, producing a political environment where the loudest and most divisive voices dominate. As a result, legislative gridlock has become routine, and public faith in Congress - already at historic lows - continues to erode. What should be the arena for reasoned debate and problem-solving has instead become a stage for partisan conflict. The consequences are far-reaching: declining institutional trust, lower civic participation, and the normalization of affective polarization, where opposing political identities are perceived not merely as rivals but as existential enemies.

Yet, the same democratic mechanisms that enable dysfunction also hold the key to reversing it. The promise of equal and free elections lies in their potential to restore moderation and accountability - if their structural integrity can be safeguarded. Reforms such as independent redistricting commissions, ranked-choice voting, open primaries, and public campaign financing are not abstract ideals; they are concrete, evidence-based strategies that can reorient incentives toward coalition-building rather than extremism. States like Maine, Alaska, and California have already demonstrated that institutional design can meaningfully influence political behavior, producing candidates who must appeal to broader constituencies and engage in more civil discourse. However, electoral reform alone is insufficient. Without a cultural commitment to cooperation and truth - shared by the media, donors, and voters themselves - even the most technically sound elections will fail to heal the democratic divide. As Barber and McCarty (2016) argue, depolarization requires not only structural change but also civic renewal: a shift in values that prioritizes compromise, empathy, and trust over perpetual conflict.

The American experience thus illustrates a crucial paradox. The country possesses one of the world’s oldest democratic constitutions, yet many of its electoral practices - such as partisan redistricting and unrestricted private campaign finance - undermine the very equality and freedom those principles were meant to secure. Free and equal elections cannot exist in name only; they must operate within an ecosystem that ensures fairness, transparency, and inclusion. When citizens believe their votes matter equally, when institutions function impartially, and when civil discourse is grounded in truth, extremism loses its oxygen.

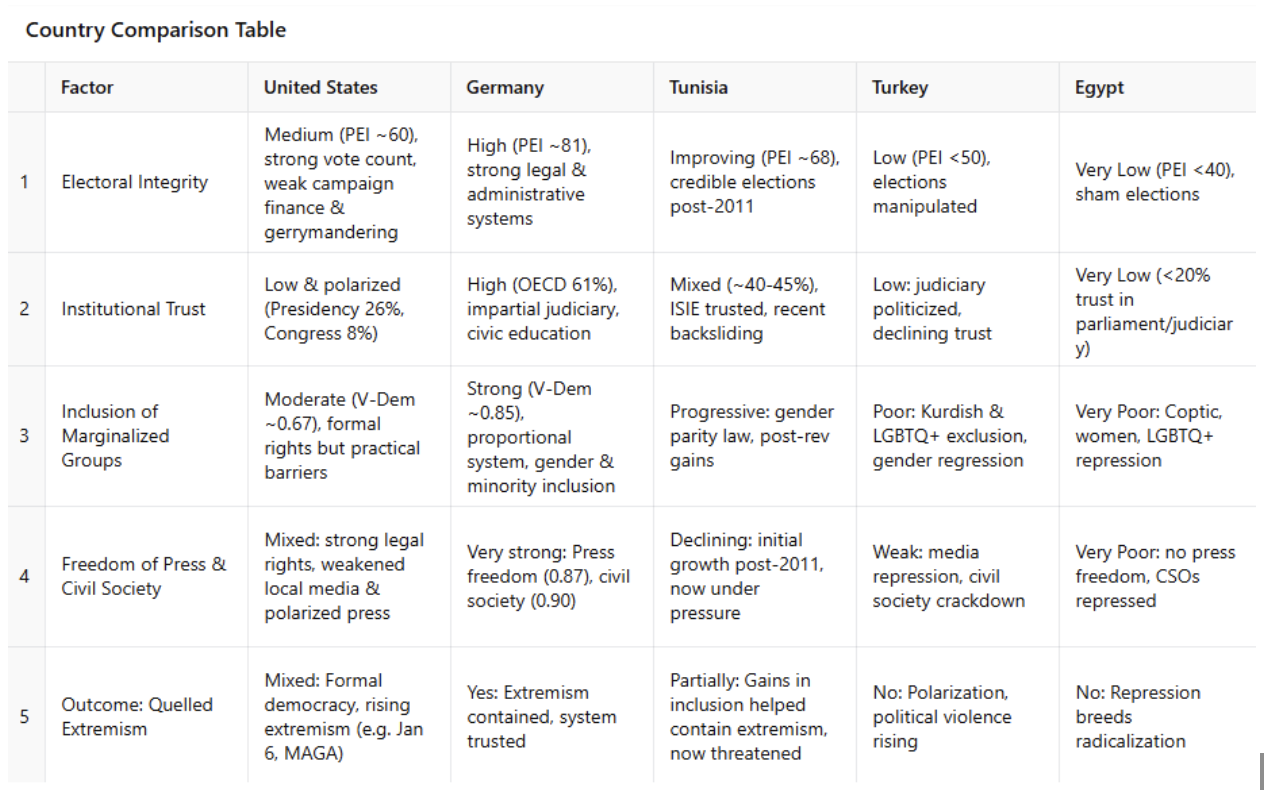

The ultimate measure in this comparative analysis is not merely whether countries hold elections, but whether those elections are meaningfully equal and free - and whether, as a result, they have succeeded in reducing political extremism. A truly equal and free election is not defined solely by the act of casting ballots; rather, it is one that is supported by four critical pillars: strong electoral integrity, robust institutional trust, meaningful inclusion of marginalized groups, and protections for press freedom and civil society. Only when these conditions are simultaneously met can elections provide the legitimacy, fairness, and representation necessary to channel public grievances into constructive democratic engagement, thereby quelling extremism and reinforcing social cohesion.

To better illustrate how these factors shape outcomes, the table below compares the five countries discussed above - Germany, Tunisia, the United States, Turkey, and Egypt - across the five key variables identified in this study.

As the table shows, Germany consistently performs at a high level across all factors. Its elections are clean, its institutions trusted, its political system inclusive, and its civic space vibrant. The result is a democratic culture where extremist movements - while not absent - are effectively kept in check. Germany’s PEI score of 81, high trust in government (61% per OECD), and V-Dem equality score of 0.85 reflect this democratic health.

Tunisia offers a more complex case. After the 2011 revolution, Tunisia made meaningful progress across several areas: it created an independent electoral commission, implemented a gender parity law, and saw an increase in civic participation. These reforms helped contain extremism by offering marginalized groups formal avenues for political expression. However, Tunisia’s recent democratic backsliding, particularly after President Kais Saied’s power consolidation in 2021, reminds us that democratic gains are not permanent. Even a promising foundation can erode without ongoing protection of democratic institutions, press freedom, and electoral independence. The U.S. must heed this warning - not only by establishing robust democratic safeguards but by ensuring they are continually enforced and protected against erosion.

In stark contrast, Turkey and Egypt illustrate what happens when elections are stripped of credibility. While elections are held regularly in both countries, they lack integrity, are conducted under authoritarian rule, and exclude large portions of the population from meaningful participation. Both rank among the lowest globally in press freedom and civil society participation. Unsurprisingly, extremism has not been curbed; rather, it has taken root either in opposition movements that feel silenced or in regimes that centralize power under the guise of stability.

Where Does the United States Stand?

The United States falls in the middle - more resilient than Turkey or Egypt, but trailing behind Germany and even Tunisia on several dimensions. It scores around 60 on the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index, well below the average for long-standing democracies. Trust in institutions has reached historic lows, with only 8% of Americans expressing confidence in Congress and 26% in the presidency, according to Gallup’s 2023 data. The V-Dem Political Equality Index places the U.S. at 0.67, indicating moderate inclusion but persistent disparities. Press freedom remains formally protected under the First Amendment, but increasing polarization, media concentration, and the rise of misinformation have eroded its democratic function. Civil society remains vibrant, yet unevenly supported and increasingly politicized at the state level.

These metrics show that while the U.S. maintains the formal architecture of democracy - elections, courts, a free press, and representative institutions - the substantive quality of those elements is under strain. Events such as the January 6 Capitol attack, widespread belief in electoral fraud, and rising political violence are not symptoms of a system lacking elections; they are symptoms of a system where elections exist without the underlying conditions that make them credible and effective tools for democratic resolution.

Thus, the American experience supports a critical conclusion: Elections must be equal and free not just in name, but in all their functional dimensions. Without electoral integrity, people believe outcomes are rigged. Without institutional trust, they stop accepting the legitimacy of results. Without inclusion, they disengage - or worse, turn to radical alternatives. And without press freedom and civic engagement, misinformation spreads unchallenged and extremist narratives flourish. Only when all four pillars are strong can elections serve as a stabilizing force and reduce the allure of extremism.

To fulfill the promise of equal and free elections as a tool for countering extremism, the United States must take deliberate and sustained action across several interrelated dimensions. First, it is essential to reinforce electoral integrity by establishing uniform federal standards for ballot access, creating independent redistricting commissions to eliminate partisan gerrymandering, and enacting serious campaign finance reforms to reduce the influence of dark money and super PACs. Without these measures, the legitimacy of electoral outcomes remains vulnerable to public skepticism and manipulation by powerful interests.

Equally important is the need to rebuild institutional trust. This requires depoliticizing key institutions - particularly the judiciary and electoral authorities - ensuring transparency in governance, and investing in professional, nonpartisan public service. When citizens believe that institutions operate fairly and independently, they are more likely to accept election outcomes and engage constructively with the political system.

Expanding political inclusion is another critical pillar. The U.S. must work to protect and enhance voting rights, particularly through the restoration of key provisions of the Voting Rights Act. It should also support the representation of historically marginalized groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, women, and LGBTQ+ individuals, and remove structural barriers that limit their access to candidacy and officeholding.

Furthermore, the protection and empowerment of civil society and independent journalism must be prioritized. This includes investing in local media to counter the growing number of news deserts, establishing transparency requirements to limit misinformation while respecting free speech, and safeguarding the right to protest and freely associate. A vibrant and independent civic sphere ensures that grievances can be expressed and addressed peacefully, preventing the kinds of vacuum that extremist movements seek to exploit.

In sum, equal and free elections are not guaranteed by the act of voting alone. They depend on a broader ecosystem of fairness, transparency, trust, and participation. Only by strengthening each of these pillars can elections fulfill their potential to reduce extremism and reinforce the long-term legitimacy of democratic governance.