Fusion Voting

Summary Overview

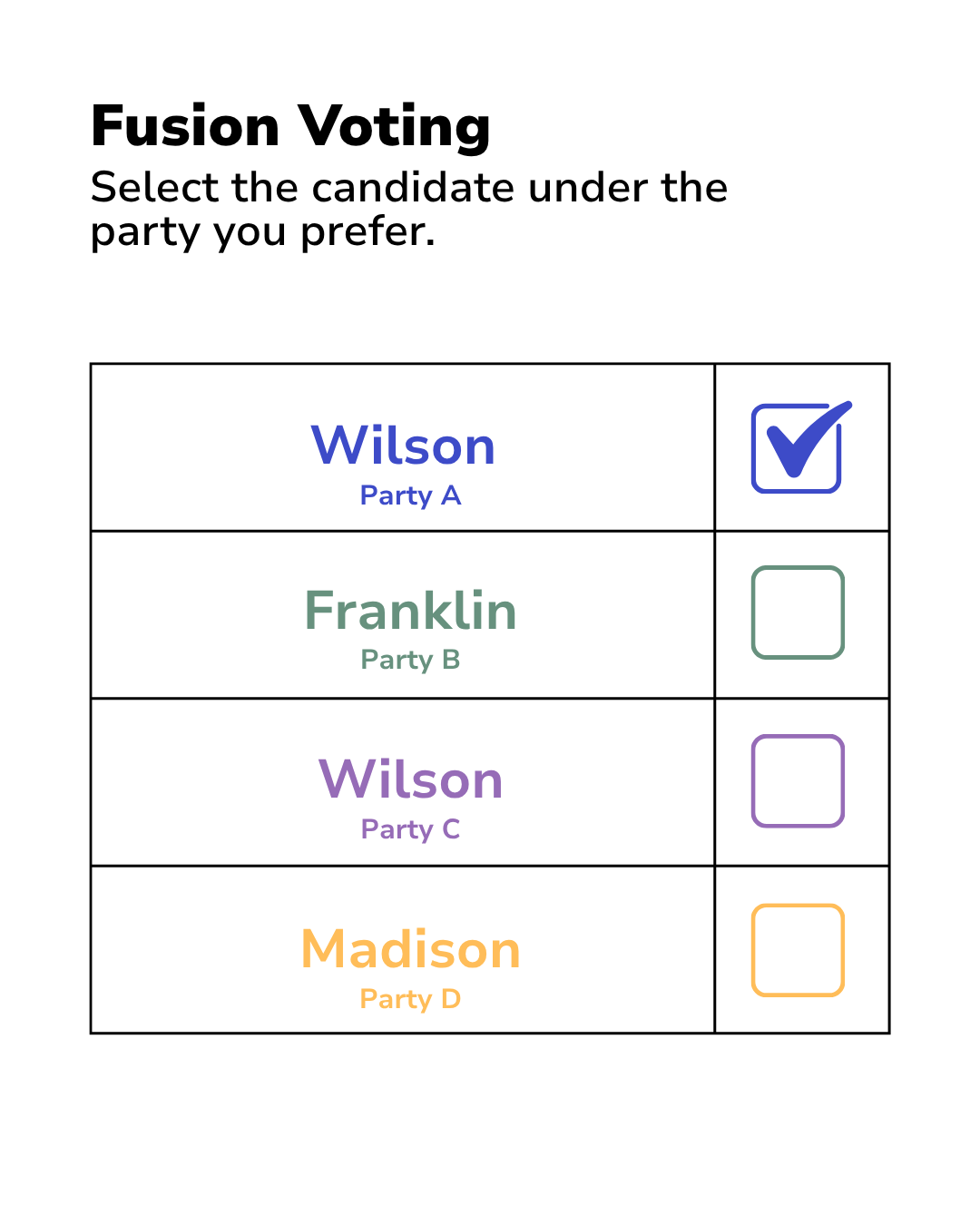

Fusion voting (also known as cross-endorsement) allows more than one political party to endorse the same candidate, with that candidate appearing on the ballot under each endorsing party's line. Supporters of fusion voting argue that it benefits minor parties by giving voters a chance to support their minor party platforms while also being able to give sympathetic candidates a greater chance at winning the election. [1] This section serves as a deeper dive into fusion voting using historical insights and evaluating how successful the implementation of the practice has been.

Supporters of fusion voting argue that this system allows for smaller parties to have more of an influence on major party platforms. Voters can support a candidate through the party label of their choice. This is said to encourage cooperation between political groups, as candidates would have to appeal to multiple groups to secure endorsements, which allows broader representation for their political base. Additionally, it has the potential to reduce gridlock, as it pushes Congress to seek common ground with minority party initiatives. However, this would only apply if the minority party has a strong coalition (i.e. Working Families Party in New York, Green Party in California).

Opponents of fusion voting make the argument that this system causes ballot confusion, because the same candidate can be listed multiple times under different parties, leading to the complication of vote counting and delaying election results. It also requires voters to be very informed about what is going on in the election and how the system works. While roughly 36% of adults do not have a four year degree, they make up about 60% of registered voters [2] [3] [4]. However, this could also raise concerns about the influence of minor parties on candidates' policy positions, especially if endorsements are perceived as contingent on adopting specific agendas [5]. Furthermore, fusion voting does not exactly offer a solution to the two party issue, primarily because it requires every minority party to have a strong presence or risk being ignored. There would also need to be sweeping changes to election laws and ballot systems across the nation, since it has been banned in all but two states–Connecticut and New York–and its main use is confined to statehouses.

Looking at how New York has used fusion voting, there have been instances where it has seemed to be useful. For instance, thanks to fusion voting, there has been legislation passed that helps with minimum wage increases as a product of lawmakers collaborating with the Working Families Party. The Working Families Party has also assisted in passing other laws, such as Tenant Protections. Fusion voting has helped establish the Campaign Finance Reform program, which reduces the reliance of big donors in elections through the small donor matching system. The initiative began in November 2022, and it allows candidates to have the ability to qualify for public matching funds based on small donations from $5 to $250 from residents in their district.

[6]. This program applies statewide.

In the 19th century, fusion voting was very common, especially among third parties like the Populist Party and Progressive Party who used it to challenge the dominance of Republicans and Democrats. The Populist Party in the 1890s often fused with Democrats to support shared candidates like William Jennings Bryan (1896) in their bid for the Presidential race.[7].

Ultimately, he lost to Republican candidate William McKinley, but with the help of the Democratic, Populist, and National Silver parties, he accumulated a total of 6,509,052 votes.[8].

Fusion was seen as a tool for grassroots movements to amplify their voices by offering their endorsement to major parties; this grants minor parties influence over policy decisions without necessarily spoiling elections. However, by the early 1900s, most states had outlawed fusion voting. In Southern states, the ban was largely due to the emergence of Jim Crow, who wanted to keep Black voters disenfranchised. In Northern states, it was mainly banned by Republican-led legislatures who wanted to prevent coalitions from being formed. A strong minority party is defined by its ability to threaten the major party's victory by running its own candidate if its demands are not met. While fusion voting still exists today, the impact is often minimal, as the results rarely show minor parties swaying electoral outcomes and policy decisions. Due to its reliance on strong minority parties, fusion voting has not yielded results impressive enough to encourage the reimplementation of this voting system nationwide.

Looking at the financial landscape of campaigns, it is evident that fusion voting has the potential to incentivize candidates to reach across multiple constituencies and fundraising networks. Candidates may expend more resources on tailored messaging and coalition-building efforts, subtly shifting financial strategies. This shift may lead to increased spending on outreach efforts tailored to the constituencies of these additional parties, such as targeted advertising, community events, and issue-specific messaging. This diversification can help reduce dependency on traditional major-party donors, though fusion voting does not inherently curb overall election spending - one of the main issues addressed by Wilson’s Fountain.

Despite its academic backing, public support for fusion voting remains limited for several reasons. First, most voters have never heard of fusion voting, as electoral reform rarely gets mainstream attention unless a major movement brings it into the spotlight. Second, the two major parties, Democrats and Republicans, have little incentive to promote a system that could weaken their power by giving smaller parties more influence. Another barrier is the lack of a well-funded advocacy movement. While organizations like the Working Families Party in New York use fusion voting effectively, there’s no large-scale public campaign to educate voters or lobby for its expansion. Additionally, some voters misunderstand the system, confusing it with vote-splitting or fearing it might create confusion, even though it actually mitigates spoiler effects. For fusion voting to gain broader public support, it would need a coordinated effort similar to the ranked-choice voting movement, including high-profile endorsements, pilot successes in more states, and sustained public education. Because of its limited potential to improve representation, fusion voting will likely remain an academic ideal rather than a widely adopted reform.

[1] Fusion voting. (n.d.). Ballotpedia. https://ballotpedia.org/Fusion_voting

[2] Hartig, H., Daniller, A., Keeter, S., & Van Green, T. (2023, July 12). Voter Turnout, 2018-2022. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/07/12/voter-turnout-2018-2022/

[3] US Census Bureau. “Census Bureau Releases New Educational Attainment Data.” Census.gov, United States Census Bureau, 2022, www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/educational-attainment.html.

[4] Pew Research Center. “Partisanship by Race, Ethnicity and Education.” Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy, Pew Research Center, 9 Apr. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/04/09/partisanship-by-race-ethnicity-and-education/

[5] “No, Fusion Voting Won’t Make Public Financing of Elections More Expensive.” Brennan Center for Justice, 2021, www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/no-fusion-voting-wont-make-public-financing-elections-more-expensive.

[6] “Program Overview.” New York State Public Campaign Finance Board, pcfb.ny.gov/program-overview.

[7] Blaine, Mary. “Rise of the Populists and William Jennings Bryan | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Www.gilderlehrman.org, www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/rise-populists-and-william-jennings-bryan.

[8] “United States Presidential Election of 1896 | United States Government | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1896.