do free and equal elections quell extremism?

by Eva Kermorgant and Bianca Silveira Ferreira

October 18, 2025

Introduction

In recent years, American politics has become increasingly defined by political extremism, where ideological divisions run deep, and cooperation across party lines seems more elusive than ever. Polarization in the U.S. has reached levels not seen in decades - according to a 2020 Pew Research Center study, 77% of Americans say that the country is more divided than in the past. This growing gulf between the two major parties has resulted in legislative gridlock.

This paper will explore the roots of political polarization, including historical, cultural, and institutional factors, and argue that the current electoral system plays a central role in fostering extreme partisanship. By examining how polarization manifests in Congress and how electoral reforms can counteract these structural drivers, this paper will show that free and equal elections are not only a moral imperative but a practical solution to reducing extremism. Ultimately, by addressing the flaws in our electoral system, we can create a political environment that encourages moderation and cooperative governance - values that benefit all Americans, regardless of party affiliation.

To better understand the conditions under which elections can either reduce or exacerbate extremism, this paper includes four international case studies - two in which democratic elections were linked to a decline in extremism, and two where elections either failed to prevent or actively contributed to its rise. They are compared under four pillars - electoral integrity, institutional trust, inclusion of marginalized groups, and freedom of press and civil society. The goal of this section is to analyse the relationship between extremism and elections abroad in order to draw lessons and conclusions for the United States.

The Congress

The United States Congress is a bicameral legislature composed of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The house has 435 members with representation based on the size of the population in each state, while the senate has 100 members consisting of two senators per state regardless of its size. This dual-chamber system was a compromise to balance the interests of populous and smaller states, ensuring that neither could dominate the legislative process (U.S. Constitution, Article I). Members of the House serve two-year terms and are elected by voters in geographically defined congressional districts, designed to promote responsiveness to public opinion and frequent accountability. Senators serve six-year staggered terms, with approximately one-third elected every two years through statewide popular vote, following the Seventeenth Amendment’s establishment of direct senatorial elections (U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 3; Seventeenth Amendment, 1913). Together, both chambers are responsible for creating, debating, and passing laws that govern critical areas such as healthcare, education, taxation, infrastructure, national defense, and civil rights. For a bill to become a law, it must pass both the House and Senate in identical form before being presented to the President for signature or veto, a process that was intended to encourage thorough deliberation and compromise. (Barber & McCarty, 2016). Additionally, the Senate holds unique powers, including confirming presidential appointments and ratifying treaties, serving as an essential check on executive authority. The House of Representatives also holds distinct responsibilities, such as initiating revenue bills and having the sole power to impeach federal officials, reinforcing its role as the chamber most directly accountable to the electorate. Congress’s legislative decisions profoundly impact nearly every facet of American life, making effective and representative governance vital to the nation’s well-being and democratic accountability.

Extremism in American Politics

However, Congress today is more divided and less productive than ever before. Increasing polarization has pushed members of both parties to opposite ends of the ideological spectrum, making bipartisan cooperation rare. As a result, Congress frequently faces legislative gridlock, where critical bills struggle to pass despite urgent public need. According to Jacobson (2013), the sharp partisan divide has led to frequent party-line voting, reducing the opportunity for compromise and moderate policymaking. The Pew Research Center (2024) highlights that a growing majority of Americans perceive Congress as ineffective, with approval ratings often dipping below 20%. This dysfunction has serious consequences: essential issues like healthcare reform, infrastructure investment, and climate policy stall, eroding public trust in the legislative branch. The persistent stalemate also discourages moderate candidates and voters, further fueling a cycle of extremism and legislative paralysis. Ultimately, this division threatens the core democratic purpose of Congress - to represent diverse viewpoints and enact laws that serve the national interest.

This pervasive legislative gridlock and the broader surge in political extremism are not random occurrences but rather the product of several interconnected and evolving factors within the American political system, its media landscape, and its broader culture. These shifts have collectively pushed the political discourse towards its ideological fringes, making moderation and bipartisan cooperation increasingly rare. A primary cause stems from a fundamental shift within the political parties themselves. Since the 1970s, there has been a noticeable loss of moderates among both Democrats and Republicans in Congress, transforming the ideological composition of the legislative body. For instance, the political center in Congress has shrunk markedly, with Brookings Institution noting it has fallen to about 10 percent of House and Senate members today, down from around 30 percent in the 1960s and 1970s.

This ideological sorting means fewer lawmakers possess the flexibility, incentive, or latitude to bridge partisan divides, leading to reduced overlap in policy preferences and a pervasive "us vs. them" mentality (Jacobson, 2013; Fleisher & Bond, 2004; Campbell, 2016). Concurrently, a phenomenon where moderates drop out of political participation has further empowered the extremes. As voters in the political middle become less engaged - perhaps due to disillusionment with gridlock or a perception of being unrepresented - the more staunchly partisan segments of the electorate gain outsized influence, particularly in low-turnout primary elections. This dynamic ensures that candidates who cater to fervent or fringe bases, rather than the broader, more moderate center, are more likely to succeed and advance to general elections (Abramowitz, 2010, "The Disappearing Center").

Beyond internal party dynamics, the modern media environment and the proliferation of misinformation have played a critical, perhaps even catalytic, role in exacerbating extremism. The rise of social media and misinformation has fractured the public into disparate and often insulated information ecosystems, where individuals increasingly inhabit distinct information bubbles and rarely agree on foundational facts, let alone interpretations of events. This technological shift enables the rapid dissemination of highly partisan or outright false narratives. Yerlikaya and Aslan (2020) highlighted how the viral spread of fake news, in particular, actively deepens these ideological divides and solidifies partisan worldviews.This phenomenon is powerfully compounded by pervasive confirmation bias online, where algorithmic feeds and individual consumption habits curate content, ensuring people predominantly encounter information that reinforces their existing beliefs and biases. For example, research on Facebook users revealed that for the median user, slightly over half of the content they saw was from politically like-minded sources, severely limiting exposure to diverse viewpoints (Syracuse University, 2023). As documented by Sunstein (2001), this leads to a "cyber-cascades" effect, where individuals are exposed to an ever-narrowing stream of reinforcing information, making it challenging to engage with opposing viewpoints or even acknowledge a shared objective reality. The impact is profound: a Pew Research study cited by YIP Institute found that 73% of Democrats and Republicans cannot even agree on basic facts. This epistemic polarization is further fueled by declining trust in traditional media. Gallup's 2024 data reveals only 31% of Americans express a "great deal" or "fair amount" of confidence in the mass media, with a stark partisan divide between 59% of Republicans who have "no trust at all" compared to just 6% of Democrats (Gallup, 2024).

Finally, the escalation of culture wars and tribalism has entrenched ideological polarization at a deeply personal and identity-based level. Republicans and Democrats are not only increasingly polarized over economic or governmental policies, but more importantly they are increasingly polarized by how their political affiliations have fused with their fundamental social and cultural identities. James E Campbell, in his 2016 book Polarized: Making sense of a divided America, elucidates this phenomenon, arguing that these identity-based and cultural divides now outweigh traditional economic cleavages in shaping political identities and loyalties. The author reveals that partisan identity has effectively transformed into a powerful social identity, where an individual’s sense of belonging and even self-worth has become intrinsically linked to their party. This “bottom-up” polarization, driven by the public rather than just elites, as Campbell identifies, intensifies group solidarity while simultaneously fueling a potent “affective polarization” - a deep-seated animosity and distrust towards the opposing side. The Pew Research Center’s 2022 report “As partisan hostility grows, signs of frustrations with the two party systems” underscores this, revealing that from 2016 to 2022, a growing share of each party described the other as closed-minded, dishonest, immoral, and unintelligent. Consequently, the very notion of compromise is reframed; it is no longer a pragmatic policy adjustment but an agonizing perceived betrayal of core values and group allegiance. This profound intertwining of political and personal identity creates significant barriers to consensus, solidifying divisions that manifest not only as policy disagreements, but as fundamental clashes of identity and worldview.

Extremism in Congress

Beyond the shifts in party composition, the fragmented media landscape and the hardening of identity-based loyalties, the very institutional structure and long-standing norms of Congress have also undergone transformational changes over the last decades, further exacerbating polarization. Historically, Congress operated with a greater emphasis on compromise, robust committee work, and regular social interaction across the aisle, fostering an environment where cooperation across ideological differences was a functional norm. However this operational ethos began to erode under new leadership styles. For instance, the Republican Revolution of the 1990’s, particularly under the assertive leadership of Newt Gingrich, ushered in a more confrontational approach. David W Rohde and Stuart Theriault (2017), in Party Polarization in Congress, argue that this period saw a critical shift where party leaders gained more power, which they then used to enforce greater party discipline and strategically structure legislative procedures to highlight partisan differences. Their research provides empirical evidence that a significant portion of the rise in party polarization has occurred via the increasing frequency of procedural votes. These procedural votes, often on motions to table, suspend rules, or limit debate, became flashpoints, demonstrating leaders’ increased ability to ensure party-line voting and block opposition initiatives. Rohde and Theriault highlight how such votes, previously less ideologically charged, became key indicators of partisan division, revealing how members ceded more control to leaders committed to advancing a unified party agenda.

Gary C Jacobson’s 2013 book, Party Polarization in American Politics, emphasizes how this era was marked by the increasing nationalization of elections, transforming congressional contests into referendums on national party leaders and platforms rather than prioritizing local issues. Jacobson demonstrates, for instance, how this nationalization led to a sharp decline in split ticket voting and a corresponding rise in straight-party voting, indicating that voters’ choices for Congress became increasingly tied to their national partisan identity rather than incumbent performance. He further argues that the strategic demonization of the opposition became a more prevalent political tactic, contributing to a legislative environment where bipartisanship was actively discouraged and seen as weakness, as parties sought to define themselves in stark contrast to their opponents in order to mobilize their bases. This profound institutional breakdown, characterized by stronger, more assertive party leadership and often hostile political discourse, has since manifested as a sharp decline in cross-party cooperation, contributing significantly to legislative paralysis and eroding public confidence in the government’s capacity to address pressing issues.

Within the United States Congress, extremism shapes the legislative body’s character and operational dynamics. This phenomenon is tied to the evolving ideological composition of its members, coupled with observable shifts in voting patterns and representational trends. One primary facet of this extremism is the increasing ideological intensity of its members, driven by two key factors. The first factor comes from Sean Thierault’s 2006 research, which sheds light on the increasing ideological divide beginning in the 1970’s within the United States Congress, particularly through the concept of the Replacement Effect. The author demonstrates that member replacement is a crucial factor of the total polarization observed in the US House and Senate. This phenomenon largely stems from the substitution of more moderate southern Democrats with increasingly conservative Republicans. As moderate voices retire or are defeated, they were replaced with more rigid ideological stances, effectively pushing the Congressional ideological center further apart. The research also highlights a decline in the number of moderates, noting that while moderates constituted 60% of Congress in 1968, this figure plummeted to just 25% in 2005. The second factor that Theriault identifies is “member adaptation,” where legislators become more ideologically extreme after being elected to Congress. Instead of new members pushing ideological boundaries, existing members who may have started as moderate become more extreme in their respective parties as they gain seniority, either as a response to electoral changes, party pressure, ideological reinforcement, and/or the desire to avoid primary challenges from more extreme candidates in their own party. However, Theriault reaffirms that although this accounts for more than a third of party polarization, it is still less impactful than the two-thirds attributed to the Replacement Effect.

The impact of this ideological shift is vividly reflected in congressional voting patterns and the overall composition of the legislature. According to Jacobson (2013), party-line votes have become the norm, with most significant legislation passing or failing strictly along partisan divides. This trend is quantitatively illustrated by DW-NOMINATE scores, a widely used measure developed by Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal, which consistently show a widening ideological gap between the two major parties. For instance, the ideological distance between the median House Democrat and median House Republican, as measured by DW-NOMINATE scores, has dramatically increased from around 0.40 in the mid-1970s to over 1.00 by the 2010s, representing a stark ideological separation (https://www.google.com/search?q=Voteview.com, updated data). This data confirms the systematic disappearance of centrists in Congress. Political scientists like Abramowitz (2010) and Fleisher and Bond (2004) have extensively documented this, noting that the percentage of "moderate" members (those whose DW-NOMINATE scores fall within a specific central range) has plummeted from over 40% in the 1970s to less than 10% in recent Congresses (https://www.google.com/search?q=Voteview.com; Abramowitz, 2010). These studies reveal a legislative landscape where the middle ground has largely evaporated, leaving a stark dichotomy between the liberal and conservative poles.

Furthermore, a distinction in polarization often exists between the two chambers. The House of Representatives tends to be more polarized than the Senate (McCarty, 2011; Fleisher & Bond, 2004). For example, in the 117th Congress (2021-2023), the average DW-NOMINATE score for ideological separation between the parties was typically higher in the House than in the Senate (https://www.google.com/search?q=Voteview.com data). This can be attributed to several factors, including the smaller, more homogenous districts represented by House members, which often allow for the election of more ideologically extreme candidates who cater to a specific partisan base. Higher turnover rates in the House also contribute to this effect; for instance, over 100 new members joined the House in both the 2010 and 2018 elections, significantly more than typically seen in the Senate, leading to new members often being more ideologically distinct than their predecessors and reinforcing the replacement effect (Congressional Research Service, 2023). The Senate, with its statewide constituencies and longer terms, theoretically encourages a broader appeal and more bipartisan compromise, though it too has experienced significant polarization.

Equal and Free Elections in the face of Extremism

The question then arises: can free and fair elections serve as a mechanism to reduce this entrenched political extremism? While the concept of democratic elections is foundational to representative governance, several aspects of the current electoral system in the United States are demonstrably broken and, arguably, contribute to the very extremism they should mitigate.

A significant structural issue is gerrymandering, where politicians manipulate electoral district boundaries to favor their own party, creating "safe seats" with little to no genuine competition (Kamarck & Galston, 2013). Research by the Brennan Center for Justice (2021) indicated that in the 2020 election cycle, an estimated 88% of House districts were uncompetitive, meaning the winning candidate secured their seat by a margin of 10 percentage points or more. FairVote (2024) further highlights that in the 2022 midterm elections, only 32 of 435 House races (about 7.4%) were decided by a margin of less than 5 percentage points, reinforcing the prevalence of safe districts. These districts are designed to ensure one party's victory, regardless of broader shifts in public opinion, effectively removing the incentive for elected officials to appeal to moderate voters or engage in bipartisan compromise. When a legislator's primary concern is fending off a challenge from their party's ideological extreme in a low-turnout primary, rather than winning over general election voters, their behavior in Congress naturally shifts towards more partisan positions.

Another contributing factor is the prevalence of closed primaries. In these elections, only registered members of a political party can vote, meaning candidates must cater to the most ideologically fervent segment of their base to secure the nomination (Abramowitz, 2010). As of 2024, 15 states operate entirely closed primary systems, and an additional 10 states have semi-closed primaries, limiting independent voter participation (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024). This system effectively pushes candidates further to the extremes, as moderate positions are unlikely to win over the core partisan voters who decide primary contests. For example, primary election turnout is often significantly lower than general election turnout; in the 2022 midterm elections, primary turnout averaged around 20-30% of eligible voters in many states, compared to over 50% for the general election (U.S. Elections Project, 2022). This allows a smaller, more ideologically committed slice of the electorate to disproportionately influence candidate selection. The Bipartisan Policy Center (2024) notes that "primary voters tend to be more partisan and ideologically extreme than the general electorate," further indicating how this system can lead to more polarized nominees. By the time the general election arrives, voters are often left with a choice between two highly polarized candidates, neither of whom may represent the political center.

Finally, the influence of big money in politics exacerbates extremism. The influx of "dark money" from undisclosed donors and the rise of Super PACs following decisions like Citizens United v. FEC (2010) allow wealthy individuals and special interest groups to funnel vast sums into campaigns, often funding highly divisive candidates and attack ads (McCarty, 2011). According to OpenSecrets.org (2024), total spending in federal elections has skyrocketed, with over $16.7 billion spent in the 2022 election cycle, a significant portion of which came from outside spending groups. "Dark money" spending by politically active non-profits (501(c)(4)s) reached over $1.2 billion in 2020, with the vast majority of these funds supporting or opposing specific candidates without disclosing their donors (OpenSecrets.org, 2021). This financial leverage incentivizes candidates to adopt extreme positions that appeal to their benefactors, further marginalizing more moderate voices and making it difficult for grassroots candidates to compete without significant financial backing.

Despite these systemic impediments, several electoral reforms have been proposed, and in some cases implemented, with the aim of mitigating extremism and fostering greater moderation and cooperation.

One promising reform is the implementation of independent redistricting commissions. By taking the power to draw electoral maps away from partisan politicians and entrusting it to non-partisan bodies, these commissions can create fairer, more competitive districts that reflect geographic and demographic realities rather than political self-interest (Kamarck & Galston, 2013). As of 2024, eight states utilize independent commissions for congressional redistricting, with several others using advisory or hybrid commissions (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024). A study by the Brennan Center for Justice (2022) found that states with independent commissions consistently produce maps with significantly less partisan bias compared to those drawn by state legislatures. For instance, in states like California and Arizona, which use independent commissions, congressional districts tend to be more competitive, as measured by typical partisan vote margins, fostering an environment where candidates must appeal to a broader electorate (FairVote, 2024).

Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV) is another reform gaining traction. In RCV, voters rank candidates in order of preference rather than choosing just one. If no candidate receives a majority of first-place votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are reallocated to the voters' next choice. This process continues until one candidate achieves a majority. RCV discourages negative campaigning and incentivizes candidates to build broader coalitions by appealing to voters beyond their base, as securing second or third-place rankings can be crucial for victory (FairVote.org). Its successful implementation in states like Maine (for federal elections since 2018) and Alaska (since 2022) demonstrates its potential to elect more moderate candidates and promote less divisive politics. In Maine's 2022 2nd Congressional District election, for example, RCV ensured the winning candidate achieved a majority, and analysis suggested it led to less negative campaigning compared to traditional elections (FairVote, 2023).

The adoption of open primaries (or non-partisan primaries) would also help broaden the base of voters in initial nominating contests, allowing independents and even members of other parties to participate (Bipartisan Policy Center, 2024). Currently, 19 states utilize fully open primary systems, while 16 states have semi-open primaries, permitting some non-affiliated voter participation (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024). The Bipartisan Policy Center (2024) argues that allowing the growing number of independent voters (which comprise over 40% of the electorate in some states like Colorado, according to Pew Research Center data) to participate in primaries could significantly dilute the influence of highly partisan factions and encourage candidates to adopt more inclusive platforms.

Finally, public campaign financing schemes aim to reduce the influence of wealthy donors and Super PACs by providing candidates with public funds to run their campaigns. This reform would enable grassroots candidates to compete effectively without relying on large contributions from special interests, thereby encouraging greater responsiveness to the general public rather than a narrow set of donors (McCarty, 2011). States like Arizona and Maine, and cities such as New York City and Seattle, have implemented various forms of public financing programs. The Brennan Center for Justice (2023) has shown that New York City's public financing system has significantly increased the diversity of candidates, with candidates of color winning 64% of publicly financed city council races compared to 36% without public funds, and has reduced the reliance on large individual donors. For instance, under NYC's program, small-dollar donors (giving $175 or less) accounted for nearly 60% of contributions to participating candidates in recent elections, demonstrating a shift towards broader citizen engagement (Brennan Center, 2023).

Complementing these established reforms, initiatives similar to what the non-profit Wilson's Fountain is proposing offer a unique, systemic approach to leverage free and equal elections against extremism. Drawing inspiration from Constitutional author James Wilson's assertion that truly "free and equal elections" are the "original fountain" of democracy, this non-profit aims to fundamentally reform the relationship between politicians and money (Wilson's Fountain, 2025). Their strategy directly addresses the "poisoning" of this fountain, particularly through gerrymandering and the pervasive influence of campaign finance. Wilson's Fountain envisions a new model of political party, not based on ideology, but on operating a truly free and equal nominating system. This system would use local committees to customize nomination processes for districts and manage uncoordinated general election campaigns for nominees via a Super PAC. By dramatically increasing constituent participation through an online, free, and equal nominating system, they believe they can elevate candidates who are genuinely motivated to serve local interests and broadly represent their constituents (Wilson's Fountain, 2025). This approach seeks to restore the voice of the people and dampen the power of money, which they identify as a primary driver of the current toxic dysfunction and extremism.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge the limits of reforms. While changes to election systems are vital, rules alone are not a panacea for the deep-seated cultural and ideological divisions that fuel political extremism (Campbell, 2016; McCarty, 2011). Simply altering voting mechanisms will not instantly repair a fractured political culture that has become accustomed to animosity and distrust. For instance, despite California's independent redistricting commission and top-two primary (a form of non-partisan primary), the state's congressional delegation still reflects significant partisan alignment, indicating that broader cultural and national political forces remain powerful.

Ultimately, a sustained effort to reduce extremism requires more than just structural adjustments to elections. There is a fundamental need to reward cooperation—a responsibility that falls not only on political leaders but also on the media, financial donors, and, most importantly, the voters themselves. As Barber and McCarty (2016) suggest, if media outlets continue to amplify divisive rhetoric, if donors continue to fund ideologically rigid candidates, and if voters continue to reward confrontational behavior, even the most well-intentioned electoral reforms will struggle to stem the tide of polarization. For free and fair elections to truly foster moderation, society must collectively shift its values to prioritize compromise, civility, and a shared commitment to functional governance over ideological purity and partisan victory. Only then can the promise of representative democracy be fully realized, moving beyond the current era of legislative gridlock and entrenched extremism.

Research has shown that when elections are influenced by gerrymandering, money, and closed primaries, political leaders are incentivized to cater to their most extreme bases rather than the broader electorate. For instance, in the post-1970s era, the number of moderate Republicans in the House dropped from 87 to just 11 by 1990, while moderate Democrats went from 109 to 52. This erosion of the political center was further amplified by the rise of social media, which a 2020 study from Yerlikaya and Aslan attributed as a major factor in fueling misinformation and deepening partisan worldviews, particularly among younger voters.

With Congress averaging only 56% of proposed legislation passed in recent years, the lowest success rate since the 1940s. More concerning, however, is the fact that this extremism is not a natural outcome of shifting political views, but rather a product of structural flaws in the electoral system. A 2021 study found that gerrymandering alone has created "safe" districts for incumbents, leading to a situation where fewer than 5% of U.S. House races are considered competitive.

Comparative Analysis

While equal and free elections are often seen as the cornerstone of democratic governance, their ability to quell political extremism depends heavily on the broader institutional and societal context in which they occur. Elections alone do not guarantee democratic resilience; rather, it is the quality, credibility, and inclusiveness of electoral processes that determine whether they channel dissent into constructive political engagement or, conversely, fuel radicalization. To assess this dynamic more systematically, this comparative analysis examines four critical dimensions that shape the relationship between electoral democracy and extremism: electoral integrity, institutional trust, inclusion of marginalized groups, and freedom of press and civil society.

This section applies these five criteria to a selection of case studies - Germany and Tunisia, which have shown relative success in reducing extremist threats through democratic means, and Turkey and Egypt, where democratic backsliding and institutional repression have coincided with persistent or growing extremism. The United States, the focal point of this study, is situated between these models: formally democratic but showing signs of institutional strain, polarization, and democratic erosion.

Through this comparative lens, the analysis aims to uncover not only how different political systems have performed across these five variables, but also what lessons the United States can draw from their successes and failures. By doing so, it offers a more nuanced understanding of when and how elections fulfill their democratic promise - and when they fall short.

Electoral Integrity

Electoral integrity refers to the extent to which elections are conducted in a free, fair, transparent, and impartial manner, adhering to international democratic standards. It encompasses elements such as voter access, accurate voter rolls, unbiased administration, and the absence of fraud or coercion. In societies grappling with political polarization or extremism, the perceived legitimacy of electoral processes plays a pivotal role in maintaining stability. When elections are seen as credible and rules are applied evenly, political actors and their supporters are more likely to channel their grievances through institutional mechanisms rather than resort to violence or anti-democratic tactics. The Electoral Integrity Project demonstrates that high electoral integrity is correlated with greater trust in institutions and lower levels of political violence, underscoring its stabilizing effect (Norris, 2014). Conversely, flawed or manipulated elections can exacerbate perceptions of injustice and marginalization, fueling extremist narratives that claim the democratic process is rigged or futile - a dynamic observed in post-election unrest in cases such as Kenya (2007) and Belarus (2020) (Birch, 2011; Wilson, 2021). Therefore, electoral integrity serves not only as a cornerstone of democratic governance but also as a key variable in either deterring or amplifying extremist sentiments.

The Electoral Integrity Project (EIP) is one of the most comprehensive international efforts to evaluate and compare the quality of elections across democratic and semi-democratic regimes. Founded by Professor Pippa Norris and hosted at institutions such as Harvard University and the University of Sydney, the EIP conducts expert surveys to generate the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index. This index scores national and subnational elections from 0 to 100 across eleven key dimensions that span the entire electoral cycle, from legal frameworks to the announcement and acceptance of results. These dimensions are designed to reflect international standards grounded in documents such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and regional charters. In its United States-specific assessment of the 2020 presidential election, the EIP gathered expert evaluations across all 50 states to measure how the U.S. compares to global best practices in electoral governance. The results present a nuanced portrait of a system that is procedurally resilient but politically vulnerable.

U.S. Performance on EIP Dimensions (2020 Election)

The first category, electoral laws, received a score of approximately 60, indicating a medium level of integrity. While the United States has a long-established legal framework governing elections, including federal statutes like the Help America Vote Act (HAVA), recent years have seen increasing politicization of election law changes at the state level. These include restrictions on mail-in voting, shortened voting periods, and legal disputes over ballot design and counting procedures, many of which are driven by partisan interests. This legal patchwork introduces inconsistencies that weaken overall legal integrity.

Electoral procedures were rated slightly higher, around 65, reflecting generally robust but uneven administration. The decentralized structure of the U.S. electoral system means that each state (and often individual counties) controls the specifics of election administration. While many jurisdictions demonstrate high professionalism and technical capacity, the lack of national standards leads to significant disparities in training, equipment, and administrative practices - particularly around absentee voting and ballot processing.

The dimension of electoral boundaries, which deals with the drawing of district lines, was one of the lower-performing categories with a score near 55. Experts highlighted persistent gerrymandering - especially in congressional and state legislative districts - as a major flaw in electoral fairness. Although some states have introduced independent redistricting commissions to mitigate partisan influence, most boundaries remain politically manipulated, undermining the principle of equal representation.

In terms of voter registration, the United States performed relatively well, scoring around 70. Initiatives such as automatic voter registration, online registration platforms, and data-sharing agreements like the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) have improved list accuracy and accessibility. Nonetheless, inconsistencies between state policies - especially regarding deadlines, purging practices, and ID requirements - still create barriers and administrative confusion.

The category of party registration received one of the highest scores, approximately 75. The U.S. maintains a relatively open environment for political party formation and competition, with few legal or procedural obstacles preventing new or third-party candidates from entering the political arena. However, systemic disadvantages - such as ballot access laws and the dominance of the two-party system - still limit practical competitiveness.

Media coverage, however, was rated poorly, with a score of around 55. Experts cited the increasingly partisan nature of mainstream media, combined with the rise of misinformation on social media platforms, as a threat to fair electoral discourse. While press freedom remains legally protected, the quality and balance of campaign coverage are often compromised by editorial biases and unregulated online content.

The weakest-performing dimension was campaign finance, with a score near 50. The U.S. system of political funding is heavily shaped by the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, which removed many restrictions on independent expenditures. The result has been a surge in "dark money," super PACs, and donor influence, which undermines transparency and creates significant imbalances between candidates with varying financial resources.

The voting process scored moderately high at 68, suggesting that access and security were relatively well maintained. Many states offered early voting, no-excuse absentee voting, and extensive voter assistance. However, disparities in ID laws, polling place availability, and voter roll accuracy continue to generate concerns - particularly in historically marginalized communities.

One of the strongest areas was the vote count, which received a high score near 80. Election officials across the country implemented rigorous tabulation procedures, including bipartisan oversight, post-election audits, and transparent reporting. Despite extensive efforts to undermine confidence in the outcome, no credible evidence of vote manipulation or fraud was found, and numerous courts upheld the integrity of the process.

The results dimension, scored at approximately 65, reflects a tension between procedural soundness and public perception. While official results were delivered in a timely and orderly manner, widespread false narratives about fraud - especially after the 2020 election - seriously eroded public trust. This disconnect between procedural integrity and public belief remains a critical vulnerability in the U.S. democratic system.

Lastly, electoral authorities received a middling score of around 60. Although federal institutions such as the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) provide guidance and support, the fact that most election officials are elected or appointed through partisan processes raises concerns about their independence. In several states, Secretaries of State played dual roles as both candidates and overseers, raising ethical questions about impartiality. This combination of formal structures and political entanglements results in what the Electoral Integrity Project classifies as “mixed independence” - a condition where electoral authorities possess some degree of institutional autonomy, but remain subject to significant influence from partisan actors. Such arrangements fall short of full independence and can undermine public confidence in the neutrality of electoral administration, especially in closely contested or polarized environments.

In summation, while the United States demonstrates resilience in core administrative processes - especially in the voting and counting stages - its overall electoral integrity is weakened by systemic issues in campaign finance, media polarization, district manipulation, and public trust. These areas collectively bring the U.S. average PEI score to approximately 60 out of 100, significantly lower than most other long-standing democracies and liberal regimes. These weaknesses illustrate how procedural democracy can coexist with substantial democratic deficits—an important point for understanding how elections alone may not be sufficient to curb political extremism.

Comparative Case Studies in Electoral Integrity

By contrast, Germany scores significantly higher, with an average PEI rating of around 81, placing it among the top-performing democracies in the world. Germany’s success is attributed to its robust legal framework, independent electoral authorities, transparent campaign financing, and strong media regulation. These factors collectively foster high levels of public confidence in the electoral process and contribute to the de-popularization of extremism.

Another instructive comparison is Tunisia, one of the few relatively successful post-Arab Spring democracies. Tunisia's PEI score is approximately 68, considerably higher than many countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. Following the 2011 revolution, Tunisia implemented significant electoral reforms, including the establishment of an independent electoral commission (ISIE) and the adoption of a new electoral law in 2014. Although challenges remain - particularly the lack of media pluralism and the lack of robust financial regulation - Tunisia has managed to hold multiple credible elections. These elections have allowed for the peaceful transfer of power and have helped contain extremist political movements by providing legitimate democratic outlets for political participation.

Comparing these two cases to the United States reveals critical gaps in the American electoral framework. Despite its longstanding democratic traditions, the U.S. trails both Germany and Tunisia in overall electoral integrity. The decentralized nature of the American electoral system creates significant inconsistencies between states in how elections are administered. While Germany has implemented strong safeguards to ensure electoral equality and independence from partisan influence, and Tunisia has made notable progress despite limited resources, both countries have taken concrete steps toward improving transparency and trust in their electoral processes. By contrast, the U.S. remains vulnerable to political manipulation through practices like gerrymandering and the pervasive influence of loosely regulated campaign financing. Although Tunisia also faces challenges with campaign finance - such as weak oversight and unequal access to resources - its issues stem more from institutional limitations than from entrenched lobbying networks or large-scale private donations, which are major factors in the American context.

In contrast, Egypt and Turkey provide examples of countries where electoral processes have failed to quell political extremism. Both countries consistently score poorly in the PEI index, typically in the 40s or lower, due to the suppression of opposition parties, constrained media environments, and the use of elections primarily as instruments of regime legitimation rather than democratic choice. In these contexts, the absence of genuine electoral competition has fueled political polarization and, in some cases, pushed dissenting voices toward more extreme or violent forms of expression.

These comparisons suggest that equal and free elections, when implemented with institutional safeguards and public legitimacy, can be powerful tools for containing political extremism. In both Germany and Tunisia, high or improving levels of electoral integrity have contributed to the stabilization of political systems and the channeling of dissent through democratic institutions. Conversely, when elections are manipulated, unfair, or distrusted - as in Egypt, Turkey, and to a lesser extent the United States - they may fail to serve as effective outlets for political grievances, increasing the risk of extremism.

To strengthen electoral integrity and democratic resilience, the United States could benefit from adopting elements of the German and Tunisian models. These include the establishment of independent redistricting commissions to prevent partisan gerrymandering, the enforcement of stricter campaign finance laws to reduce undue influence, and the creation of uniform federal standards for voting accessibility and security. Additionally, improved media regulation and public education about election processes could help rebuild trust in the system. Ultimately, as this comparative analysis shows, free and equal elections are not only democratic ideals - they are essential mechanisms for mitigating political extremism, provided they are supported by the institutional conditions that make them credible in the eyes of the public.

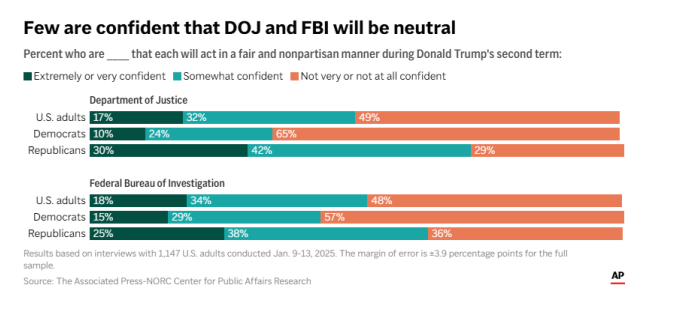

Importantly, these varying levels of institutional trust have become strongly correlated with political identity. A 2022 report by the American National Election Studies (ANES) found that Republican trust in government dropped to just 13% following the 2020 election (when Joe Biden (D) won the presidential race) compared to 45% among Democrats. This was a complete reversal from the 2016 election, when Democrats’ trust was low and Republican trust was comparatively high (when Donald Trump (R) was elected). This oscillation indicates an unstable foundation of trust in institutions and conditional trust based on partisan control. Such volatility makes democratic institutions vulnerable to manipulation, delegitimization, and anti-system narratives, especially during electoral transitions or periods of political scandal.

Furthermore, institutional trust is highly stratified along racial, socioeconomic, and generational lines. Black and Latino Americans, for example, have historically exhibited lower trust in law enforcement and the justice system due to systemic discrimination, over-policing, and inequities in legal outcomes (Pew Research Center, 2022; Pew Research Center, 2024). At the same time, younger Americans (ages 18–29) report the lowest trust in government of any age group, according to Pew (2023), citing climate inaction, student debt, and lack of representation as key grievances.

Comparative Case Studies in Institutional Trust

Germany demonstrates considerably higher levels of institutional trust. The OECD 2023 report ranks trust in the German government at 61%, significantly above the U.S. average. Germany’s political institutions benefit from a strong federal system with checks and balances, professional civil service, and a Constitutional Court widely perceived as impartial. Transparent policymaking and consistent rule enforcement have helped preserve public confidence, even amid political disagreements. Importantly, Germany has actively addressed past authoritarian legacies through civic education, institutional reforms, and a commitment to democratic accountability. These efforts have strengthened the legitimacy of the system and reduced the appeal of anti-system extremism.

Tunisia, while not without challenges, offers another instructive case. In the years following the 2011 revolution, Tunisia launched a national transitional justice process - including the Truth and Dignity Commission (established 2013–14) - and pushed forward significant civic participation initiatives like public consultations in constitutional drafting and the decentralization of political power to local municipalities. These efforts aimed to rebuild institutional trust by addressing past abuses, engaging citizens directly in governance, and distributing authority beyond the central state. Trust in the Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE) has remained relatively high compared to other government bodies, being considered a credible arbiter of democratic competition. While overall trust in Tunisian institutions remains mixed - hovering around 40–45% depending on the institution and survey year - this is still notable in the regional context, where trust in state institutions is typically much lower. The presence of relatively trusted electoral and judicial institutions has helped provide a democratic outlet for dissent, mitigating the risk of radicalization.

In contrast, Egypt and Turkey exhibit low levels of institutional trust, which correlates with the persistence of authoritarianism and heightened political extremism. In Egypt, the government under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has systematically repressed civil society, restricted media freedom, and undermined judicial independence. According to Arab Barometer (2022) data, trust in Egypt’s parliament is below 20%, and confidence in the judiciary is also low, undermined by perceptions of politicization and lack of accountability. Similarly, in Turkey, under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, trust in government and judiciary institutions has plummeted due to widespread purges, media crackdowns, and the centralization of power. The World Values Survey reports that Turkish citizens' trust in parliament and political parties has declined sharply in recent years, with growing segments of the population viewing the political system as unresponsive or corrupt.

The experiences of Germany and Tunisia offer valuable lessons for the United States on how to rebuild and sustain institutional trust. Both cases demonstrate that trust can be cultivated through transparency, fairness, and efforts to include citizens in democratic decision-making. Germany’s investment in civic education, independent judiciary, and professional public administration (referring to merit-based, well-resourced, and politically neutral state institutions) serves as a model for restoring credibility. While the U.S. also has a large network of state and federal agencies, trust in these institutions has declined due to factors such as politicization, inconsistent service delivery, and perceptions of bureaucratic inefficiency. Tunisia, despite economic and political instability, shows that even fragile democracies can strengthen trust when institutions function with relative independence and openness. The U.S. could benefit from reinforcing institutional neutrality - particularly in law enforcement and judicial appointments - alongside empowering watchdog bodies and ethics enforcement mechanisms to expose and penalize misconduct, ensuring that powerful actors cannot operate above the law or manipulate democratic institutions unchecked.

Conversely, Egypt and Turkey serve as cautionary tales. In both cases, institutional decay and repression of dissent have created vacuums filled by extremism, conspiracy theories, and political violence. For the United States, continued erosion of governmental trust - especially when fueled by disinformation and political attacks on oversight institutions - risks similar destabilizing effects. Avoiding this path requires defending institutional autonomy, depoliticizing electoral and judicial bodies, and fostering public engagement through meaningful civic education and transparency.

Inclusion of Marginalized Groups

Democratic systems are strengthened when they are inclusive - particularly of groups historically excluded from political, economic, or social life. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), inclusive political processes are essential to democratic resilience because they ensure marginalized populations have a voice in public decision-making. These groups can include ethnic and religious minorities, women, the LGBTQ+ community, indigenous peoples, rural populations, and economically disadvantaged citizens. Political exclusion and systemic discrimination are common drivers of extremism, as they often lead to a sense of hopelessness or injustice that radical movements can exploit. Free and equal elections are a primary channel through which inclusion can be institutionalized - whether through proportional representation, accessible voting systems, political outreach, or, in some contexts, reserved seats for minority groups. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance notes that more than 30 countries have adopted minority quotas or reserved seats in their legislatures as a strategy for political inclusion. Examples include India (for different castes and tribes), New Zealand (Māori seats), and Colombia (Afro-Colombian and Indigenous representation). When marginalized communities see themselves reflected in political power structures and decision-making processes, the appeal of extremist ideologies tends to diminish. As highlighted by UNDP and USAID, inclusive governance offers peaceful pathways to address grievances, thereby reducing the likelihood that individuals turn to extremism.

To measure this dimension internationally, one of the most referenced databases is the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, which includes specific indicators under its Equal Protection Index and Political Equality Index. These sub-indices assess the extent to which individuals from different social groups enjoy equal political power and influence, as well as legal protections. V-Dem’s approach is grounded in a multidimensional view of democracy and relies on expert-coded assessments for consistency and global comparability. It provides disaggregated data on group inclusion, including access to civil liberties, representation in legislatures, and protections against discrimination. Additionally, the Gender Quota Database - maintained by International IDEA, the Inter-Parliamentary Union, and Stockholm University - offers insights into formal mechanisms like candidate quotas, which require political parties to nominate a minimum percentage of women on their electoral lists, and reserved seats, which guarantee a fixed number of legislative positions for women regardless of electoral outcomes. These mechanisms are widely used, and as of 2023, over 130 countries have adopted some form of gender quota.

According to V-Dem’s 2023 data, the United States ranks relatively high on formal inclusion metrics, such as universal suffrage and legal anti-discrimination protections. However, it lags behind many high-income democracies on effective inclusion and equitable political representation. For instance, the U.S. Political Equality Index (2023) score is 0.67 on a 0–1 scale, reflecting a moderate level of inclusion with significant room for improvement. While laws prohibit explicit discrimination in voting, systemic inequalities and structural barriers continue to limit genuine political participation for many groups.

While the United States may perform reasonably well on paper - thanks to constitutional guarantees, civil rights legislation, and anti-discrimination statutes - the practical enforcement of these protections often falls short. Legal frameworks alone are insufficient when the institutions responsible for upholding them are themselves implicated in perpetuating inequality. For instance, institutions such as law enforcement agencies and election officials - tasked with safeguarding equal access and civil rights - have historically engaged in practices that suppress minority political participation. While the most overt forms of disenfranchisement, like literacy tests and white-only primaries (which excluded Black voters from participating in primary elections), were outlawed during the civil rights era, more subtle tactics persist today. These include reducing the number of polling places in minority neighborhoods, imposing strict voter ID laws, and purging voter rolls - all of which disproportionately affect communities of color. Studies by the Brennan Center for Justice and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights have documented how such measures contribute to unequal access to the ballot. This disconnect between democratic ideals and uneven implementation fosters a credibility gap, undermining public trust in institutions that claim to uphold equal rights. It also highlights the importance of not only enacting inclusive policies but ensuring they are implemented equitably and without bias. In short, the presence of anti-racist laws does not guarantee an anti-racist system - especially when those tasked with applying the law operate within structures shaped by decades of racial inequality.

Racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. - especially Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities - face enduring obstacles in political participation, including voter suppression tactics such as purging of voter rolls, gerrymandering of minority districts, strict voter ID laws, and limited polling access in minority neighborhoods. The 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, has been widely criticized for weakening federal oversight of discriminatory practices at the state level.

According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, women’s representation in U.S. politics has grown but remains comparatively low. As of 2023, women hold around 29% of seats in Congress - below the global average for national parliaments and far behind countries with gender quotas or proportional systems. The situation is more dire for intersectional representation: Black, Latina, Asian, Indigenous, and LGBTQ+ women are significantly underrepresented in elected office, with women of color holding less than 10% of congressional seats (CAWP).

Despite increasing visibility, the LGBTQ+ community faces legislative backlash in many states, including restrictions on gender-affirming care and the inclusion of queer topics in education. These developments contribute to a political climate that discourages full civic participation and representation, even when formal legal rights exist.

The exclusion of racial and ethnic minorities from full political participation has far-reaching consequences for American politics. When these communities encounter systemic barriers - such as voter suppression, underrepresentation, and discriminatory districting - they often become disillusioned with traditional democratic processes. This erosion of trust contributes to lower voter turnout, weaker civic engagement, and a growing perception that political institutions do not serve their interests. In some cases, this marginalization has fueled support for outsider candidates or movements that promise radical change, disrupting conventional party coalitions and reshaping the political landscape. For instance, both left-wing and right-wing populist movements have capitalized on the grievances of underrepresented groups - either by mobilizing them with promises of justice and reform, or, conversely, by exploiting racial and cultural anxieties to suppress their influence or redirect blame. At the same time, many rural and lower-income white communities have been drawn to right-wing populist movements like the MAGA coalition, feeling abandoned by mainstream political elites and excluded from national economic and cultural narratives. In these cases, perceived exclusion - not only from material resources but from political recognition - has also driven radicalization. The resulting polarization further entrenches exclusion, creating a feedback loop that undermines democratic legitimacy. Addressing the political exclusion of minority communities is therefore not only a matter of equity but a crucial step in restoring faith in democratic governance and preventing the drift toward extremism.

Comparative Case Studies in Inclusion of Marginalized Groups

Germany performs considerably better on indicators of political inclusion. V-Dem ranks Germany at 0.85 on the Political Equality Index, citing strong anti-discrimination laws, inclusive political party structures, and high levels of gender and minority representation. Germany’s use of proportional representation encourages diversity among elected officials, and the federal government has adopted national strategies to promote the political participation of immigrants, disabled persons, and ethnic minorities (Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2017). As of 2023, nearly 35% of Bundestag members are women, and the number of legislators with migrant backgrounds continues to grow. These efforts contribute to the perception that democratic institutions are open and representative - limiting the appeal of anti-systemic extremism.

Tunisia also presents a notable example of progress. Following its 2011 revolution, Tunisia implemented a vertical gender parity law requiring party lists to alternate between male and female candidates, resulting in one of the highest percentages of women in parliament in the Arab world (41% in the 2019 election). The Tunisian constitution also enshrines rights for people with disabilities and commits to combatting racial discrimination. However, challenges persist: political inclusion of Black Tunisians and the Amazigh community remains limited, and recent authoritarian backsliding threatens the gains of the post-revolutionary period. Nevertheless, Tunisia’s early reforms demonstrate how institutional change can foster participation and dampen extremist impulses by empowering long-excluded groups.

In contrast, Egypt and Turkey illustrate the risks of exclusionary governance. In Egypt, political power remains concentrated in the hands of military elites, and opposition parties, civil society organizations, and minority groups face severe repression. The Coptic Christian minority and other religious groups face restrictions in representation and expression. Women’s participation is limited by both legal hurdles and social norms, and LGBTQ+ individuals face criminalization and persecution. V-Dem ranks Egypt among the lowest globally on group equality and inclusion, scoring below 0.3 on the Political Equality Index.

Turkey exhibits similar trends. Although the country has held regular elections, President Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian rule has narrowed space for political dissent. The pro-Kurdish HDP (People’s Democratic Party) has been systematically targeted, with its leaders imprisoned and members expelled from parliament. Minority inclusion - especially for Kurds, Armenians, and LGBTQ+ communities - has declined sharply. Gender parity has also deteriorated, especially after Turkey’s 2021 withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention on gender-based violence.

The United States can draw valuable lessons from both positive and negative examples. Like Germany and Tunisia, the U.S. could implement institutional reforms to improve representativeness and remove barriers to participation. Conversely, the U.S. must avoid the path taken by Egypt and Turkey, where exclusionary governance, repression of dissent, and erosion of civil liberties undermine political inclusion and fuel extremism. Ignoring or suppressing the voices of marginalized communities does not eliminate discontent - it redirects it into more radical channels, as numerous studies have shown that political exclusion and perceived injustice are key drivers of extremism and support for anti-establishment movements (UNDP, 2016; Schmid, 2013).

Ultimately, inclusion is not merely a moral imperative; it is a pragmatic strategy for democratic resilience. Ensuring that all citizens see themselves represented and respected in democratic institutions reduces the appeal of extremist ideologies and strengthens the social contract. A truly inclusive democracy is a more stable and peaceful one.

Freedom of Press and Civil Society

A free press and an active civil society are vital components of democratic ecosystems. They serve as watchdogs, forums for civic dialogue, and channels through which citizens can express dissent without resorting to violence. Independent media can expose corruption, highlight policy failures, and amplify marginalized voices, contributing to greater accountability and transparency in governance. Likewise, civil society organizations (CSOs) - such as Transparency International, which combats global corruption, or Legal Resources Centre in South Africa, which provides pro bono legal assistance to marginalized groups - can mobilize communities, monitor elections, and advocate for reforms. When these freedoms are protected, elections are more likely to be informed, participatory, and credible - thereby reducing the allure of extremist solutions. However, when governments suppress the press or restrict civil society, misinformation proliferates, grievances go unaddressed, and political polarization deepens. Extremist actors often flourish in such vacuums, filling the gap left by weakened democratic institutions. Thus, the health of press freedom and civil society directly influences whether elections foster democratic resilience or deepen political fragmentation and extremism.

To measure these dimensions internationally, the V-Dem project offers a robust and methodologically transparent assessment. Hosted by the University of Gothenburg and drawing on expert surveys from thousands of country specialists, V-Dem compiles indices that reflect the health of media freedom, civil society participation, and other democratic attributes. Two indices are especially relevant here: the “Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information” index and the “Civil Society Participation” index. These indicators assess not only formal rights, such as legal protections for journalists or NGOs, but also de facto conditions - including media independence, harassment levels, access to diverse viewpoints, and the ability of civil organizations to operate without state interference.

According to V-Dem data (2023), the United States presents a mixed picture. On the “Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources” index, the U.S. scored 0.77 on a scale from 0 (least free) to 1 (most free), indicating relatively strong legal protections but increasing concern over media polarization, economic pressures on journalism, and the rise of disinformation. The U.S. fared better in the “Civil Society Participation” index, scoring 0.85, reflecting the country’s long tradition of robust civic engagement and a high density of NGOs, community organizations, and advocacy movements. However, the V-Dem data also flag signs of deterioration over the past decade - particularly a rise in political polarization and state-level legal efforts to restrict protest rights and civil society activity. Early data from 2025 suggest these trends have accelerated under the current administration, with watchdog groups like CIVICUS and Freedom House noting increased constraints on media independence and civic organizing.

In terms of press freedom, the U.S. benefits from First Amendment protections, which prohibit censorship and protect journalists from legal reprisals. Nevertheless, these formal protections coexist with mounting challenges. Economic consolidation in media markets has diminished local journalism, while partisan outlets and algorithmic amplification on social media have deepened echo chambers and fueled disinformation. The phenomenon of “news deserts” - regions with little to no local reporting - further undermines informed civic participation. Additionally, the harassment of journalists - especially those covering protests or political scandals - has increased, with several high-profile arrests or attacks during demonstrations drawing concern from watchdog groups like Reporters Without Borders.

Civil society in the U.S. remains vibrant but unevenly empowered. Movements such as Black Lives Matter and March for Our Lives demonstrate the continued ability of grassroots activism to shape national debates. However, recent years have seen rising tensions between protestors and state authorities. Laws in states like Florida and Oklahoma have expanded penalties for participating in protests deemed “disruptive,” raising concerns about chilling effects on free assembly. Furthermore, political polarization has led to differential treatment of civil society groups, with some organizations labeled as “extremist” or “un-American” depending on the governing party. These dynamics suggest that while civil society remains a potent force, its capacity to serve as a democratic stabilizer is increasingly contested.

Comparative Case Studies of Freedom of Press and Civil Society

In contrast, Germany performs strongly on both V-Dem indices, scoring 0.87 for press freedom and 0.90 for civil society participation. German media is governed by stringent public broadcasting standards, diverse ownership, and clear regulations on political advertising and campaign coverage. The country's Press Council enforces ethical journalism, and constitutional protections for both media and CSOs are broadly respected. Importantly, Germany also enforces legislation such as the Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (NetzDG) to curb hate speech and misinformation on social media platforms, without significantly undermining press independence. Civil society in Germany benefits from active government cooperation and funding, as well as a strong legal framework that protects NGOs, unions, and advocacy groups. These conditions enable citizens to voice dissent, debate policy, and participate meaningfully in democratic life - factors that have helped contain the appeal of extremist ideologies.

Tunisia, though facing significant democratic backsliding in recent years, had demonstrated important gains in this domain during the post-2011 transition period. From 2011 to around 2019, Tunisia’s V-Dem score for press freedom rose to 0.62 and civil society participation to 0.68 - remarkable improvements in a region often characterized by state control. Independent outlets flourished, and watchdog NGOs like Al Bawsala played a crucial role in monitoring government transparency. However, since President Kais Saied’s consolidation of power in 2021, these gains have been under threat. Critics note increased pressure on journalists and the use of military courts to try civilians, including civil society leaders. Still, Tunisia’s prior experience highlights the positive impact of empowering non-state actors to counterbalance political forces and channel public concerns away from violence.

By contrast, Egypt and Turkey illustrate how undermining press and civil society freedom can accelerate extremism and authoritarianism. Egypt scores just 0.19 in press freedom and 0.23 in civil society participation - among the lowest globally. Independent journalism is virtually nonexistent, with major outlets controlled by the state or allied business entities. NGOs operate under restrictive laws, and dozens of civil society activists remain imprisoned or harassed. In Turkey, President Erdoğan’s government has systematically eroded media independence, jailing journalists, shuttering opposition outlets, and using “insulting the president” laws to stifle dissent. Civil society, once a vibrant force in the early 2000s, has also been constricted through arrests, surveillance, and administrative burdens on NGOs. In both countries, the lack of legitimate outlets for dissent has driven opposition either into exile, into apathy, or into radical, sometimes militant, alternatives.

These comparisons yield clear insights for the United States. Germany and (to some extent) Tunisia demonstrate how robust protections for media and civil society contribute to democratic legitimacy and reduce the allure of extremist alternatives.

Strong civil organizations and independent journalism not only inform and engage citizens but also serve as pressure valves for discontent, channeling opposition into constructive forms. The U.S. can take inspiration from Germany’s effective media regulation and institutional support for civil society - without infringing on constitutional freedoms. Simultaneously, Egypt and Turkey highlight the dangers of undermining these freedoms: when citizens cannot trust information or organize peacefully, democratic channels collapse, and extremism can thrive.

To enhance its democratic resilience, the United States should invest in revitalizing local journalism, limiting excessive media consolidation by enforcing ownership caps and promoting diversity of outlets, and countering disinformation through public education and platform accountability. Protecting the rights of protestors and removing barriers to NGO operations - especially at the state level - are also critical. Ultimately, a well-informed and civically engaged public is the strongest antidote to political extremism, and that foundation rests on the twin pillars of press freedom and civil society.

Conclusion

The rise of political extremism in the United States cannot be understood in isolation from the structural features of its electoral system. Over the past decades, factors such as gerrymandering, closed primaries, the influence of dark money, and the decline of moderates have fundamentally distorted representation in Congress. These mechanisms reward ideological rigidity and punish compromise, producing a political environment where the loudest and most divisive voices dominate. As a result, legislative gridlock has become routine, and public faith in Congress - already at historic lows - continues to erode. What should be the arena for reasoned debate and problem-solving has instead become a stage for partisan conflict. The consequences are far-reaching: declining institutional trust, lower civic participation, and the normalization of affective polarization, where opposing political identities are perceived not merely as rivals but as existential enemies.

Yet, the same democratic mechanisms that enable dysfunction also hold the key to reversing it. The promise of equal and free elections lies in their potential to restore moderation and accountability - if their structural integrity can be safeguarded. Reforms such as independent redistricting commissions, ranked-choice voting, open primaries, and public campaign financing are not abstract ideals; they are concrete, evidence-based strategies that can reorient incentives toward coalition-building rather than extremism. States like Maine, Alaska, and California have already demonstrated that institutional design can meaningfully influence political behavior, producing candidates who must appeal to broader constituencies and engage in more civil discourse. However, electoral reform alone is insufficient. Without a cultural commitment to cooperation and truth - shared by the media, donors, and voters themselves - even the most technically sound elections will fail to heal the democratic divide. As Barber and McCarty (2016) argue, depolarization requires not only structural change but also civic renewal: a shift in values that prioritizes compromise, empathy, and trust over perpetual conflict.

The American experience thus illustrates a crucial paradox. The country possesses one of the world’s oldest democratic constitutions, yet many of its electoral practices - such as partisan redistricting and unrestricted private campaign finance - undermine the very equality and freedom those principles were meant to secure. Free and equal elections cannot exist in name only; they must operate within an ecosystem that ensures fairness, transparency, and inclusion. When citizens believe their votes matter equally, when institutions function impartially, and when civil discourse is grounded in truth, extremism loses its oxygen.

The ultimate measure in this comparative analysis is not merely whether countries hold elections, but whether those elections are meaningfully equal and free - and whether, as a result, they have succeeded in reducing political extremism. A truly equal and free election is not defined solely by the act of casting ballots; rather, it is one that is supported by four critical pillars: strong electoral integrity, robust institutional trust, meaningful inclusion of marginalized groups, and protections for press freedom and civil society. Only when these conditions are simultaneously met can elections provide the legitimacy, fairness, and representation necessary to channel public grievances into constructive democratic engagement, thereby quelling extremism and reinforcing social cohesion.

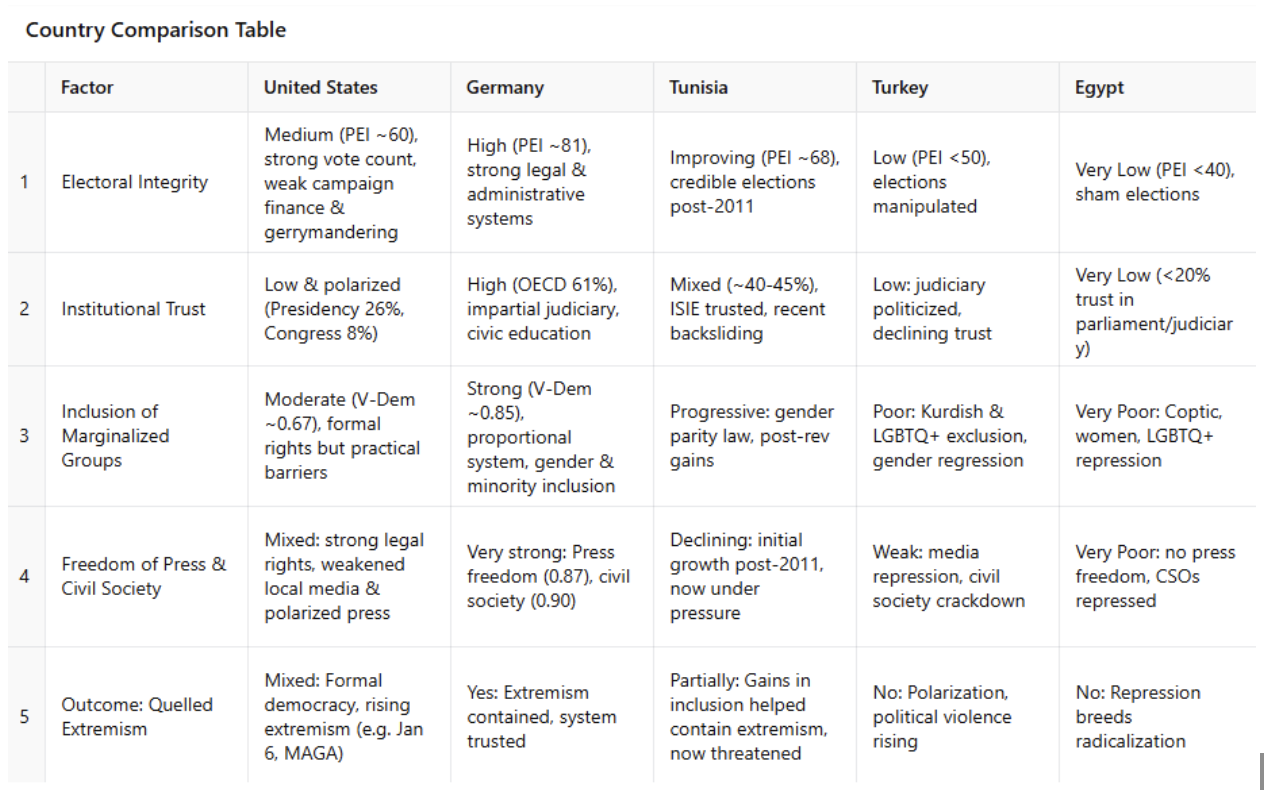

To better illustrate how these factors shape outcomes, the table below compares the five countries discussed above - Germany, Tunisia, the United States, Turkey, and Egypt - across the five key variables identified in this study.

As the table shows, Germany consistently performs at a high level across all factors. Its elections are clean, its institutions trusted, its political system inclusive, and its civic space vibrant. The result is a democratic culture where extremist movements - while not absent - are effectively kept in check. Germany’s PEI score of 81, high trust in government (61% per OECD), and V-Dem equality score of 0.85 reflect this democratic health.

Tunisia offers a more complex case. After the 2011 revolution, Tunisia made meaningful progress across several areas: it created an independent electoral commission, implemented a gender parity law, and saw an increase in civic participation. These reforms helped contain extremism by offering marginalized groups formal avenues for political expression. However, Tunisia’s recent democratic backsliding, particularly after President Kais Saied’s power consolidation in 2021, reminds us that democratic gains are not permanent. Even a promising foundation can erode without ongoing protection of democratic institutions, press freedom, and electoral independence. The U.S. must heed this warning - not only by establishing robust democratic safeguards but by ensuring they are continually enforced and protected against erosion.

In stark contrast, Turkey and Egypt illustrate what happens when elections are stripped of credibility. While elections are held regularly in both countries, they lack integrity, are conducted under authoritarian rule, and exclude large portions of the population from meaningful participation. Both rank among the lowest globally in press freedom and civil society participation. Unsurprisingly, extremism has not been curbed; rather, it has taken root either in opposition movements that feel silenced or in regimes that centralize power under the guise of stability.

Where Does the United States Stand?