Ranked Choice Voting

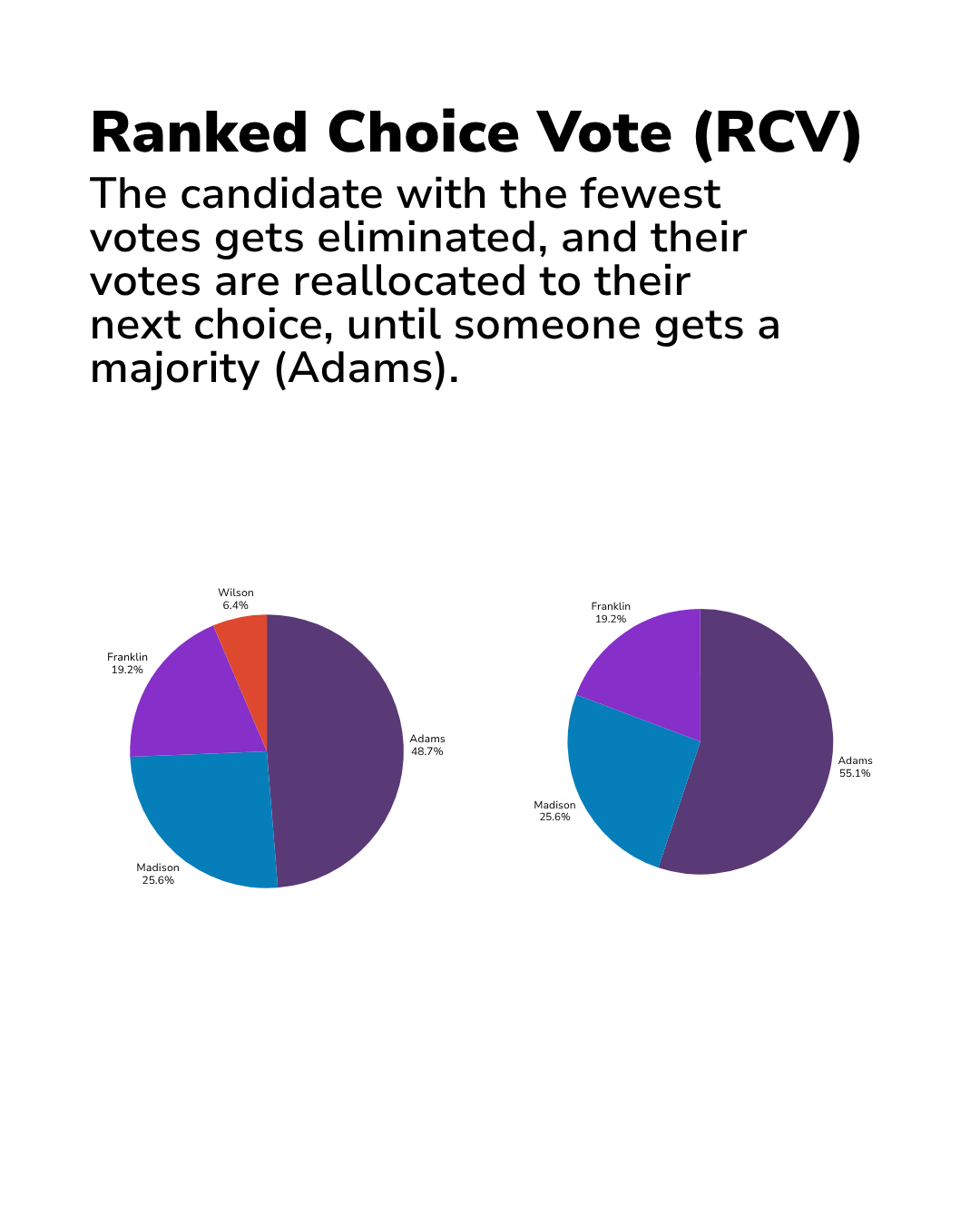

Summary Overview Ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank all candidates in order of preference instead of just choosing one. There are often multiple rounds. When the lowest-ranked candidates are eliminated, votes for those candidates are rolled into voters’ second choices until one candidate has a majority of the votes. This means that whichever candidate wins has broad support from the majority of voters, allowing for more representative outcomes. Ranked-choice voting also eliminates the problem of wasted votes, as even if a voter’s first choice does not win, their vote automatically counts for their next ranked choice. Ranked-choice voting is currently used in 63 jurisdictions across 24 states, including party-run primaries, special elections, and ballots for military and overseas voters in federal runoffs. [15]

Analysis

Ranked-choice voting is increasingly being implemented in cities across the country, and has proven to get more diverse candidates elected. [16] In ranked-choice voting races, people of color often gain more support through subsequent vote rounds than white candidates, with Black candidates increasing their vote share by 15% compared to 12% for white candidates. One major success with ranked-choice voting is that it often generates higher turnout and higher voter satisfaction. When used in the New York 2021 primaries, the election had its highest turnout in the last 30 years.[17] It has also shown to have an impact on youth participation, as young people often want options outside of the two major parties but feel it is pointless to turn up in our current “first past the post” (FPTP) voting system. Juelich & Coll (2021) survey data showed younger voters were 9 percentage points more likely to vote in RCV cities than plurality cities. [18] However, other studies show decreased participation, especially among low-income voters and voters with low levels of education. This may be because RCV can cause voter confusion and result in spoiled ballots.

[16] Otis, D., & Laverty, S. (2024, January 16). Ranked choice voting elections benefit candidates and voters of color: 2024 Update - FairVote. https://fairvote.org/report/communities-of-color-2024/

[17] Fair Vote. (n.d). Research and data on RCV in practice - FairVote. https://fairvote.org/resources/data-on-rcv/

[18] Juelich, C. L., & Coll, J. A. (2021). Ranked Choice Voting and Youth Voter Turnout: The Roles of Campaign Civility and Candidate Contact. Politics and Governance, 9(2), 319-331. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i2.3914

[19] Fair Vote. (n.d). Research and data on RCV in practice - FairVote. https://fairvote.org/resources/data-on-rcv/

[20] Otis, D., Wilburn, Y., Huang, B., & Reisman, A. (2025, June 25). Once again, ranked choice voting improved New York City elections. FairVote. https://fairvote.org/once-again-ranked-choice-voting-improved-new-york-city-elections/

[21] The New York Times. (2023, February 17). Alaska U.S. Senate election results. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/11/03/us/elections/results-alaska-senate.html

[22] New York City to launch $15 million ranked Choice Voting Education campaign. (2021, April 28). The official website of the City of New York. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/315-21/new-york-city-launch-15-million-ranked-choice-voting-education-campaign

[23] Fair Vote. (n.d). Research and data on RCV in practice - FairVote. https://fairvote.org/resources/data-on-rcv/

[24] Rhode, C. (n.d.). The cost of ranked choice voting. https://esra.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1556/2020/11/rhode.pdf